In Part I, we defined narrative, plot and story. Let’s explore these in an example.

Allow me to tell you a story:

Tuyen saw Jackie on the sidewalk through the window of the cafe. It had been one year since they ended things. Tuyen lifted her hand to knock on the window, but then saw her own reflection.

It had been ten years since she first worked up the courage to kiss Jackie, at night, in the rain, under the awning of a video store.

Tuyen hesitated. She watched Jackie boarding the downtown bus. And then, she was gone.

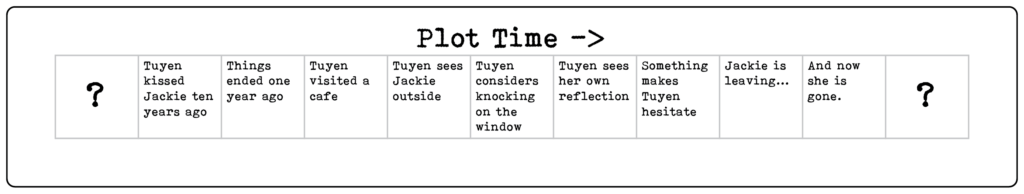

This is a narrative. If we were to lay it out in the order of the plot, it would look like this:

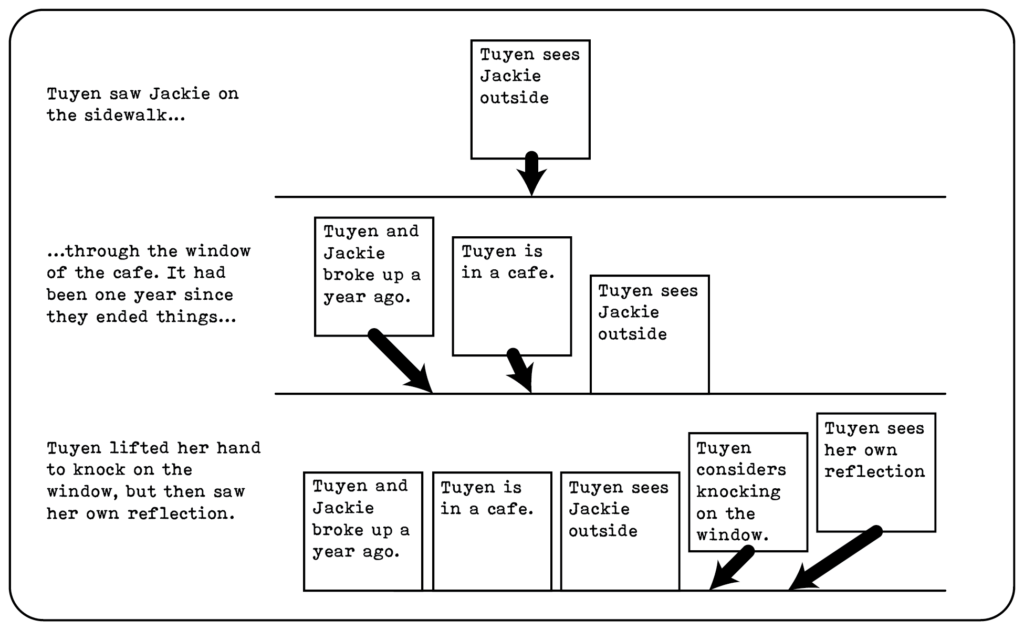

If we wanted, we could visualize the way the narrative delivers the plot, one piece at a time, not starting at the beginning, and not always in order.

To really understand story, we have to remember that story is as much about how we experience the narrative as it is some final product.

The audience enjoys making some guesses about how things connect and where things might be going. Keith Johnstone calls this the Circle of Probability. Pixar’s Andrew Stanton calls it the Unifying Theory of 2+2.

The narrative, above, lays out several events without explicitly explaining cause and effect. Some narratives do. I could have narrated, “Tuyen hesitated because she was afraid it had been too long,” for instance. But in this case, I wanted the audience to decide the exact nature of the cause and effect themselves.

So! Here’s how I might experience this story. How is it different than how you experienced it?

- Someone named Tuyen (Maybe a Vietnamese woman?) sees someone named Jackie (Probably a woman?) on the sidewalk (okay, we’re in an urban area) through the window or cafe. (Perhaps they are meeting or maybe on a date?)

- It has been a year since they broke up… (Oh, okay, maybe they haven’t seen each other?)

- Tuyen lifts her hand to knock on the window… (I feel a narrative pause here… I wonder how she feels? How does Jackie feel?)

- She sees her own reflection. (I wonder what she sees. Age? An emotion? A scar?)

- Her reflection somehow makes her think about ten years ago, and about being afraid to kiss Jackie. (Maybe she noticed she’s older? They must have been together for a long time. I wonder if it is important that Tuyen has had to overcome fear in the past, maybe she’s feeling similar now?)

- She hesitates. (Why? It might be fear, since we just explored that. Or insecurity over her appearance? Or maybe it’s wisdom and choosing to let things go?)

- Jackie is boarding the bus… (Another narrative pause here–this gives me a feeling of urgency, is Tuyen going to stop her?)

- She’s gone. (The moment has passed. How does Tuyen feel? Sad? Lonely? Comfortable? How do I feel? What does this make me think of in my life?)

Your story probably changed as you read the narrative, and it was probably different than mine. Story includes your experiences, your mood, your subconscious associations, and countless other things mean that you will always have a different story than your neighbor.

The storyteller can’t (and shouldn’t) control most of this… but they can influence it. More importantly, perhaps, they can leave space for it!

In the narrative above, I chose to drag a couple of moments out long enough for the reader to formulate story. If I didn’t want the reader to spend much time creating story at this point, the narrative could have read

“Tuyen saw her Jackie, her ex, walk by the cafe. She thought about flagging Jackie down, but changed her mind and went back to her tea.”

The plot is the same (although less detailed), but the full experience of the story is very different.

How different may depend on the style.

In Part III of this article, we will start to explore how an improviser or director might apply the principles, in practice.

Tony Beeman has lived in Seattle as a writer, performer, director and software developer since 1998. In addition to performing, directing and serving as Artistic Associate at Unexpected Productions in Pike Place Market, Tony performs regularly with 4&20 Improv, Seattle Experimental Theater, and Improv Anonymous. He has taught workshops in seven countries. His Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is INFP.